A Word On Structure And Form

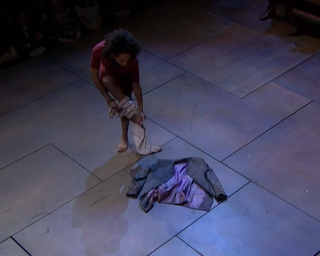

In case you haven't had enough examination feedback, I'm sharing even more: this time on the first part of the exam question which invited you to discuss the passage from Act 1 Scene 2, lines 65-120, exploring Shakespeare's use of language and its dramatic effects.

This scene is a gift, as it offers Hamlet’s first words and actions of the play.

Because it is Shakespeare, of course they are rich with imagery and ideas that set up all sorts of themes and

conflicts for the rest of the play - so there is plenty to discuss. You are interested in how Shakespeare shapes meaning through the interplay of language, form and structure. It is, in many ways, easier to deal with all three together, since that word 'interplay' is quite important.

Because it is Shakespeare, of course they are rich with imagery and ideas that set up all sorts of themes and

conflicts for the rest of the play - so there is plenty to discuss. You are interested in how Shakespeare shapes meaning through the interplay of language, form and structure. It is, in many ways, easier to deal with all three together, since that word 'interplay' is quite important.

Form is really concerned with aspects of genre that appear within a text, as well as the 'form,' or type, of the text itself, in this case a play, and specifically, a Shakespearian tragedy. Form might also include the physical form or organisation of the text; for our purposes in this extract, the blank verse and iambic pentameter.

Structure involves investigating the framework of a text, or the 'architecture' of it, including its sequence of events, how they are revealed, and how they are all threaded together. Structure involves structural 'devices', which might include narrative manipulation techniques like foreshadowing, analepsis and prolepsis, perhaps repetition. It may require you to focus on time itself. In the course of the play, this might take you into the territory of classical unities and how they are handled by the playwright. (Oh, so we might actually be dealing with form, in that case - I refer you back to the 'interplay' idea!) But while you are focusing on a passage, it is as though you are in a little room of the house (or castle!) which will have its own 'architecture' as well as being part of the larger building.

So, I will take you through some of the things that occurred to me as I was reading the passage. Assume that I am 'doing' language, unless it is highlighted in bold. In which case try to work out whether I am 'doing' form or structure, or both.

The extract is rich with imagery and ideas which foreground the later tragedy, establishing many of the protagonist's major preoccupations in relation to death while beginning to explore the tensions between appearance and reality, and, at the same time, exposing his conflict with Claudius and his unhappiness with Gertrude.

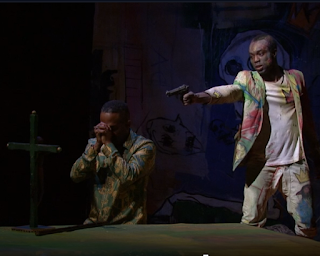

Claudius addresses Hamlet directly, emphasising their new, doubly-entwined relationship as both 'cousin' (a word that Shakespeare used to denote any kind of family tie - Hamlet would have been Claudius' nephew before the marriage) and now, following Claudius' marriage to Gertrude, his 'son'. Having spent a scene and a half manipulating the audience's expectations about Hamlet, this section of the text sees Hamlet finally deliver his first line, in response, and as an 'aside' at that. His first action is both to challenge this false representation of their relationship - and also to establish his capacity for word-play which creates a kind of intellectual superiority. He plays with the root of 'kin' and 'kind', managing to suggest that Claudius is both unkind and unnatural. This piece of information is shared only with the audience, and not to the rest of the court, helping to position us 'beside' Hamlet, and therefore identify with him.

When Claudius asks about why the 'clouds still hang', Hamlet replies with a direct contradiction, 'not so' and again chooses to play with words, returning the weather metaphor back to Claudius while manipulating the homophonic similarities between 'sun' and son' to suggest that being in this relationship displeases him.

Gertrude then intervenes, perhaps in an effort to release the palpably mounting tension. These are also her first words in the drama. Like Claudius', they are rebuffed by Hamlet. She too questions the extent of his mourning and obvious melancholy, but the use of her word 'common' is also picked up and thrown back, 'Ay madam, it is common', signalling discord in this relationship, too. It is a discord that Gertrude seeks immediately to repair, since she 'share's Hamlet's line to complete the iambic rhythm with 'if it be' and thereby attempts to restore harmony between them.

Gertrude continues to placate him and seeks further explanation about the depths of his grief. Hamlet identifies a concern that will resonate throughout the play: the difference between what is and what seems to be, or between being and seeming. His words suggest that he alone is motivated by a deeper grief, and establish his gloomy, philosophical tendencies.

Claudius then engages once more with some patronising repetition relating to 'fathers'. He seems first to actively goad Hamlet, then moves to warning, and accusations of naivety, 'an understanding simple and unschooled'. This falls flat since Hamlet's intellectual dominance has already been established. Claudius suggests that death is to be accepted as a natural part of life, and Hamlet should be able to move on. He offers what could be perceived as an unwitting reference to Cain and Abel, a Biblical reference which alludes to the 'first' murder and violence enacted by one brother on another in the reference to 'the first corse' - thereby echoing the action of the play itself. As yet, of course, the audience know nothing about the circumstances of Hamlet's father's death, but Claudius is nevertheless established as an untrustworthy character in conflict with the hero.

The extract concludes with Claudius' request that Hamlet not return to his studies in Wittgenstein, which allows Hamlet to deliver a final insult by ignoring his step-father's entreaty and responding instead to Gertrude. 'All my best to obey you, madam'. His rebuttal of Claudius is complete.

Let me know if that is helpful. More on blank verse and iambic pentameter coming soon.

The extract is rich with imagery and ideas which foreground the later tragedy, establishing many of the protagonist's major preoccupations in relation to death while beginning to explore the tensions between appearance and reality, and, at the same time, exposing his conflict with Claudius and his unhappiness with Gertrude.

Claudius addresses Hamlet directly, emphasising their new, doubly-entwined relationship as both 'cousin' (a word that Shakespeare used to denote any kind of family tie - Hamlet would have been Claudius' nephew before the marriage) and now, following Claudius' marriage to Gertrude, his 'son'. Having spent a scene and a half manipulating the audience's expectations about Hamlet, this section of the text sees Hamlet finally deliver his first line, in response, and as an 'aside' at that. His first action is both to challenge this false representation of their relationship - and also to establish his capacity for word-play which creates a kind of intellectual superiority. He plays with the root of 'kin' and 'kind', managing to suggest that Claudius is both unkind and unnatural. This piece of information is shared only with the audience, and not to the rest of the court, helping to position us 'beside' Hamlet, and therefore identify with him.

When Claudius asks about why the 'clouds still hang', Hamlet replies with a direct contradiction, 'not so' and again chooses to play with words, returning the weather metaphor back to Claudius while manipulating the homophonic similarities between 'sun' and son' to suggest that being in this relationship displeases him.

Gertrude then intervenes, perhaps in an effort to release the palpably mounting tension. These are also her first words in the drama. Like Claudius', they are rebuffed by Hamlet. She too questions the extent of his mourning and obvious melancholy, but the use of her word 'common' is also picked up and thrown back, 'Ay madam, it is common', signalling discord in this relationship, too. It is a discord that Gertrude seeks immediately to repair, since she 'share's Hamlet's line to complete the iambic rhythm with 'if it be' and thereby attempts to restore harmony between them.

Gertrude continues to placate him and seeks further explanation about the depths of his grief. Hamlet identifies a concern that will resonate throughout the play: the difference between what is and what seems to be, or between being and seeming. His words suggest that he alone is motivated by a deeper grief, and establish his gloomy, philosophical tendencies.

Claudius then engages once more with some patronising repetition relating to 'fathers'. He seems first to actively goad Hamlet, then moves to warning, and accusations of naivety, 'an understanding simple and unschooled'. This falls flat since Hamlet's intellectual dominance has already been established. Claudius suggests that death is to be accepted as a natural part of life, and Hamlet should be able to move on. He offers what could be perceived as an unwitting reference to Cain and Abel, a Biblical reference which alludes to the 'first' murder and violence enacted by one brother on another in the reference to 'the first corse' - thereby echoing the action of the play itself. As yet, of course, the audience know nothing about the circumstances of Hamlet's father's death, but Claudius is nevertheless established as an untrustworthy character in conflict with the hero.

The extract concludes with Claudius' request that Hamlet not return to his studies in Wittgenstein, which allows Hamlet to deliver a final insult by ignoring his step-father's entreaty and responding instead to Gertrude. 'All my best to obey you, madam'. His rebuttal of Claudius is complete.

Let me know if that is helpful. More on blank verse and iambic pentameter coming soon.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteWell, it's that interplay thing. If you really want to separate them, I think 'tragedy' is definitely form, 'aside' is structural, and the iambic pentameter could be either depending on what you are saying - in that particular example I think I would say it's structurey. How have I just found myself saying 'structurey'?

ReplyDeleteNo!

ReplyDelete