Godwin's 2016 RSC Production: Act Three

As we move into Act III (which is the longest part of this production running at 44 minutes), the stage is draped in enormous canvases, hanging down from the ceiling and spread across the floor. They suggest Hamlet's mania from their volume, and the preoccupations of his troubled mind in the calligramatic references to serpents, crowns and skulls. The concept of the tortured artist is constructed visually before it is enacted.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern's incompetence is suggested through their casual behaviour at the start of the scene, giving the idea that they don't really have their minds on the job, but are treating their time here as a holiday.

Essiedu's Hamlet embarks on the 'To be or not to be' speech with a plaintive, questioning tone. You can explore the RSC's approach to this in more depth here.

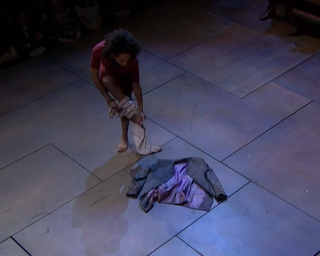

When Ophelia enters she is evidently still smarting from their previous exchange and attempts to return a large box of gifts and keepsakes from their relationship. Hamlet's 'No' initially draws a laugh from the audience, who are soon silenced by the threat of physical and sexual violence that follows. He tosses the trifles to the floor dismissively. Ophelia is then picked up, forcibly carried across the stage and flung to the floor. On the word 'calumny' Hamlet smears her face in green paint. Then she is thrown down onto the bed and Hamlet climbs on top of her while she tries to writhe away - signifying the threat of rape in an all too visceral way. It is a deeply disturbing scene to watch for the audience.

Claudius, too, is unsettled by what he has seen and heard, hidden behind one of the artworks. He also uses Hamlet's discarded canvas to highlight the melancholy 'in his soul'. Polonius is distraught at the treatment of his daughter - but his next plan seems grasping and ineffectual, to contrive to overhear another conference.

At the start of scene ii, the intimacy between Hamlet and Horatio is clear - perhaps even more so since its tenderness contrasts with the brutality of what has just gone before, which gives greater weight and threat to the 'country matters' exchange with Ophelia. Hamlet's feigned madness is signalled through the wearing of a bizarre dragon-like headdress. Gertrude and Claudius are unimpressed, and Hamlet's flippant responses are not well-received.

Hamlet takes an active role in performance as a drummer, and later as a kind of narrator. His directing of the action is also seen in his command of 'centre stage' at the start. The vulnerability of the Player King is emphasised in his reliance on a zimmer frame. He is no match for the villainous Lucianus.

A female Guildenstern now works to feeds Hamlet's rage against the 'frailty' of woman. He grabs her face in an echo of the way he treated Ophelia in the previous scene.

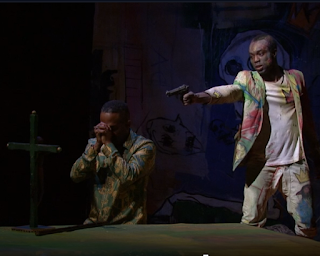

In the closing soliloquy he reaches once more for the revolver - on the 'hot blood' line. Now with far greater purpose and intent than in Act One - yet unable to murder Claudius when he comes across him attempting prayer. He looms out of the shadows in a stealthy, menacing way but can't carry out the deed.

Alone with his mother, he makes the comparison between the old king, his father - tattooed onto his chest and thereby across his heart - with the new murderous king who fronts the cover of a glossy magazine - a facade for a poor imitation of his predecessor. The murder of Polonius is over in a second, a rash gunshot at what Hamlet believes to be Claudius hiding. The swift drop of the curtain is dramatic and like a guillotine - an execution, tragically, of the wrong man.

Comments

Post a Comment