Changing Interpretations Over Time: G H Lewes

I always like it when a man is introduced in reference to his more famous partner (though sadly it usually happens the other way round.) In this case, George Henry Lewes (1817-1878) is actually better known for being the partner or 'companion' of Mary Ann Evans - herself better known as George Eliot.

By the time Eliot was writing, some female authors were being published under their own names but she chose to escape the stereotypes surrounding women's writing and its supposed limitations by choosing a male-sounding name. She also wished to have her fiction judged separately from her writing as an editor and literary critic. The magnificent Middlemarch is an epic summer holiday read if you need one. Martin Amis, eminent novelist in his own right, describes it as being 'the' novel of the 19th century', and a group of international critics decided that it was the best novel of all time back in 2015. Quite a claim indeed.

Anyway, I digress. We're here to talk about her less famous partner - although it is thought that another factor in her use of a pen name may have been a desire to protect her private life from public scrutiny, thereby avoiding scandal: George Henry Lewes was a married man.

I know!

He did have something to say about Hamlet, though.

G. H. LEWES (companion of George Eliot): from 'Life and Works of Goethe', 1855

Hamlet, in spite of a prejudice current in certain circles that if now produced for the first time it would fail, is the most popular play in our language. It amuses thousands annually, and it stimulates the minds of millions. Performed in barns and minor theatres oftener than in Theatres Royal, it is always and everywhere attractive. The lowest and most ignorant audiences delight in it. The source of the delight is twofold:

First, its reach of thought on topics the most profound; for the dullest soul can feel a grandeur which it cannot understand, and will listen with hushed awe to the out-pouring of a great meditative mind obstinately questioning fate;

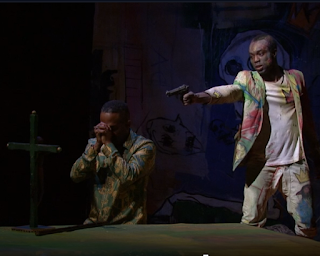

Secondly, its wondrous dramatic variety. Only consider for a moment the striking effects it has in the Ghost; the tyrant murderer; the terrible adulterous queen; the melancholy hero, doomed to so awful a fate; the poor Ophelia, broken-hearted and dying in madness; the play within a play, entrapping the conscience of the King; the ghastly mirth of the gravediggers; the funeral of Ophelia interrupted by a quarrel over her grave betwixt her brother and her lover; and, finally, the horrid bloody denouement. Such are the figures woven in the tapestry by passion and poetry.

Add thereto the absorbing fascination of profound thoughts. It may indeed be called the tragedy of thought, for there is as much reflection as action in it; but the reflection itself is made dramatic, and hurries the breathless audience along, with an interest which knows no pause. Strange it is to notice in this work the indissoluble union of refinement with horrors, of reflection with tumult, of high and delicate poetry with broad, palpable, theatrical effects. The machinery is a machinery of horrors, physical and mental: ghostly apparitions - hideous revelations of incestuous adultery and murder - madness - Polonius killed like a rat while listening behind the arras - gravediggers casting skulls upon the state and desecrating the churchyard with their mirth - these and other horrors form the machinery by which moves the highest, the grandest, and the most philosophic of tragedies.

What are the key ideas in Lewes' argument? Summarise them in your own words.

Might any still have resonance today? Why/not? Give examples from Hamlet to support your ideas.

How does this compare with some of the perspectives that we have read previously?

Is there a memorable, standout phrase?

By the time Eliot was writing, some female authors were being published under their own names but she chose to escape the stereotypes surrounding women's writing and its supposed limitations by choosing a male-sounding name. She also wished to have her fiction judged separately from her writing as an editor and literary critic. The magnificent Middlemarch is an epic summer holiday read if you need one. Martin Amis, eminent novelist in his own right, describes it as being 'the' novel of the 19th century', and a group of international critics decided that it was the best novel of all time back in 2015. Quite a claim indeed.

Anyway, I digress. We're here to talk about her less famous partner - although it is thought that another factor in her use of a pen name may have been a desire to protect her private life from public scrutiny, thereby avoiding scandal: George Henry Lewes was a married man.

I know!

He did have something to say about Hamlet, though.

G. H. LEWES (companion of George Eliot): from 'Life and Works of Goethe', 1855

Hamlet, in spite of a prejudice current in certain circles that if now produced for the first time it would fail, is the most popular play in our language. It amuses thousands annually, and it stimulates the minds of millions. Performed in barns and minor theatres oftener than in Theatres Royal, it is always and everywhere attractive. The lowest and most ignorant audiences delight in it. The source of the delight is twofold:

First, its reach of thought on topics the most profound; for the dullest soul can feel a grandeur which it cannot understand, and will listen with hushed awe to the out-pouring of a great meditative mind obstinately questioning fate;

Secondly, its wondrous dramatic variety. Only consider for a moment the striking effects it has in the Ghost; the tyrant murderer; the terrible adulterous queen; the melancholy hero, doomed to so awful a fate; the poor Ophelia, broken-hearted and dying in madness; the play within a play, entrapping the conscience of the King; the ghastly mirth of the gravediggers; the funeral of Ophelia interrupted by a quarrel over her grave betwixt her brother and her lover; and, finally, the horrid bloody denouement. Such are the figures woven in the tapestry by passion and poetry.

Add thereto the absorbing fascination of profound thoughts. It may indeed be called the tragedy of thought, for there is as much reflection as action in it; but the reflection itself is made dramatic, and hurries the breathless audience along, with an interest which knows no pause. Strange it is to notice in this work the indissoluble union of refinement with horrors, of reflection with tumult, of high and delicate poetry with broad, palpable, theatrical effects. The machinery is a machinery of horrors, physical and mental: ghostly apparitions - hideous revelations of incestuous adultery and murder - madness - Polonius killed like a rat while listening behind the arras - gravediggers casting skulls upon the state and desecrating the churchyard with their mirth - these and other horrors form the machinery by which moves the highest, the grandest, and the most philosophic of tragedies.

What are the key ideas in Lewes' argument? Summarise them in your own words.

Might any still have resonance today? Why/not? Give examples from Hamlet to support your ideas.

How does this compare with some of the perspectives that we have read previously?

Is there a memorable, standout phrase?

Comments

Post a Comment