Changing Interpretations Over Time: Samuel Johnson

It's not surprising that Shakespeare tops the league as the most quoted Englishman of all time; nor that Hamlet is the most often quoted of his plays.

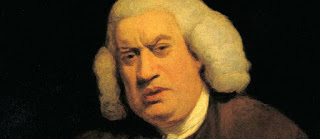

But Samuel Johnson, as well as being recognised amongst the most highly regarded literary figures in the eighteenth century, is regularly credited as being the second most-quoted after Shakespeare.

And of course, most famous for compiling the first dictionary of the English Language in 1755. You can find out more about him here.

Aside from being a handsome fellow, poet, lexicographer, essayist, and a big list of other things, he was a literary critic who wrote this about Hamlet:

SAMUEL JOHNSON: from his edition of Shakespeare's plays, 1765

IF the dramas of Shakespeare were to be characterised, each by the particular excellence which distinguishes it from the rest, we must allow to the tragedy of Hamlet the praise of variety. The incidents are so numerous, that the argument of the play would make a long tale. The scenes are interchangeably diversified with merriment and solemnity; with merriment that includes judicious and instructive observations, and solemnity, not strained by poetical violence above the natural sentiments of man. New characters appear from time to time in continual succession, exhibiting various forms of life and particular modes of conversation. The pretended madness of Hamlet causes much mirth, the mournful distraction of Ophelia fills the heart with tenderness, and every personage produces the effect intended, from the apparition that in the first act chills the blood with horror, to the fop in the last, that exposes affectation to just contempt.

The conduct is perhaps not wholly secure against objections. The action is indeed for the most part in continual progression, but there are some scenes which neither forward nor retard it. Of the feigned madness of Hamlet there appears no adequate cause, for he does nothing which he might not have done with the reputation of sanity. He plays the madman most, when he treats Ophelia with so much rudeness, which seems to be useless and wanton cruelty.

Hamlet is, through the whole play, rather an instrument than an agent. After he has, by the stratagem of the play, convicted the King, he makes no attempt to punish him, and his death is at last affected by an incident which Hamlet has no part in producing.

The catastrophe is not very happily produced; the exchange of weapons is rather an expedient of necessity, than a stroke of art. A scheme might easily have been formed, to kill Hamlet with the dagger and Laertes with the bowl.

The poet is accused of having shown little regard to poetical justice, and may be charged with equal neglect of poetical probability. The apparition left the regions of the dead to little purpose; the revenge which he demands is not obtained but by the death of him that was required to take it; and the gratification which would arise from the destruction of an usurper and a murderer, is abated by the untimely death of Ophelia, the young, the beautiful, the harmless, and the pious.

So, same questions for Johnson as for Voltaire:

What are the key ideas in his argument? Summarise them in your own words.

Might any still have resonance today? Why/not?

Is there a memorable, standout phrase here?

But Samuel Johnson, as well as being recognised amongst the most highly regarded literary figures in the eighteenth century, is regularly credited as being the second most-quoted after Shakespeare.

And of course, most famous for compiling the first dictionary of the English Language in 1755. You can find out more about him here.

Aside from being a handsome fellow, poet, lexicographer, essayist, and a big list of other things, he was a literary critic who wrote this about Hamlet:

SAMUEL JOHNSON: from his edition of Shakespeare's plays, 1765

IF the dramas of Shakespeare were to be characterised, each by the particular excellence which distinguishes it from the rest, we must allow to the tragedy of Hamlet the praise of variety. The incidents are so numerous, that the argument of the play would make a long tale. The scenes are interchangeably diversified with merriment and solemnity; with merriment that includes judicious and instructive observations, and solemnity, not strained by poetical violence above the natural sentiments of man. New characters appear from time to time in continual succession, exhibiting various forms of life and particular modes of conversation. The pretended madness of Hamlet causes much mirth, the mournful distraction of Ophelia fills the heart with tenderness, and every personage produces the effect intended, from the apparition that in the first act chills the blood with horror, to the fop in the last, that exposes affectation to just contempt.

The conduct is perhaps not wholly secure against objections. The action is indeed for the most part in continual progression, but there are some scenes which neither forward nor retard it. Of the feigned madness of Hamlet there appears no adequate cause, for he does nothing which he might not have done with the reputation of sanity. He plays the madman most, when he treats Ophelia with so much rudeness, which seems to be useless and wanton cruelty.

Hamlet is, through the whole play, rather an instrument than an agent. After he has, by the stratagem of the play, convicted the King, he makes no attempt to punish him, and his death is at last affected by an incident which Hamlet has no part in producing.

The catastrophe is not very happily produced; the exchange of weapons is rather an expedient of necessity, than a stroke of art. A scheme might easily have been formed, to kill Hamlet with the dagger and Laertes with the bowl.

The poet is accused of having shown little regard to poetical justice, and may be charged with equal neglect of poetical probability. The apparition left the regions of the dead to little purpose; the revenge which he demands is not obtained but by the death of him that was required to take it; and the gratification which would arise from the destruction of an usurper and a murderer, is abated by the untimely death of Ophelia, the young, the beautiful, the harmless, and the pious.

So, same questions for Johnson as for Voltaire:

What are the key ideas in his argument? Summarise them in your own words.

Might any still have resonance today? Why/not?

Is there a memorable, standout phrase here?

Comments

Post a Comment