Changing Interpretations Over Time: Goethe

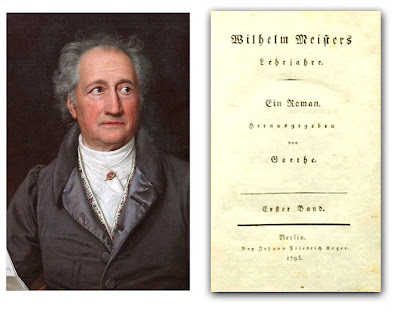

If nothing else, our foray into criticism of Hamlet is providing us with a who's who of literary greats in Europe. Next up is Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), widely considered to be Germany's greatest literary figure - and clearly a man who knew a thing or two about sporting a frock coat, judging by his picture.

You may have come across him already as he is also credited with writing the first Bildungsroman in Willhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

By the 1740s, Shakespeare's work had begun to be translated into German, and, by the end of the eighteenth century, had achieved great popularity and influence in Germany.

In Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship the protagonist, Wilhelm sets out on his travels after being disillusioned in love - and is introduced to the works of Shakespeare by the character Jarno before playing the lead role in a theatrical production of Hamlet. Much discussion of Shakespeare's work takes place within the dialogue of the novel, thus revealing something of the eighteenth-century German reception of Shakespeare's plays. It is Wilhelm who speaks the following words in the novel, generally considered to represent Goethe's views:

J. W. VON GOETHE: from Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship

The time is out of joint, O curs'd spite,

That ever I was born to set it right!

In these words, I imagine, will be found the key to Hamlet's whole procedure. To me it is clear that Shakespeare meant, in the present case, to represent the effects of a great action laid upon a soul unfit for the performance of it. In this view the whole piece seems to me to be composed. There is an oak-tree planted in a costly jar, which should have borne only pleasant flowers in its bosom; the roots expand, the jar is shivered.

A lovely, pure, noble and most moral nature, without the strength of nerve which forms a hero, sinks beneath a burden which it cannot bear and must not cast away. All duties are holy for him; the present is too hard. Impossibilities have been required of him; not in themselves impossibilities, but such for him. He winds, and tums, and torments himself; he advances and recoils; is ever put in mind, ever puts himself in mind; at last does all but lose his purpose from his thoughts; yet still without recovering his peace of mind.

So, usual prompts:

What are the key ideas in Wilhelm's (Goethe's) argument? Summarise them in your own words.

Might any still have resonance today? Why/not?

Is there a memorable, standout phrase here?

You may have come across him already as he is also credited with writing the first Bildungsroman in Willhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

By the 1740s, Shakespeare's work had begun to be translated into German, and, by the end of the eighteenth century, had achieved great popularity and influence in Germany.

In Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship the protagonist, Wilhelm sets out on his travels after being disillusioned in love - and is introduced to the works of Shakespeare by the character Jarno before playing the lead role in a theatrical production of Hamlet. Much discussion of Shakespeare's work takes place within the dialogue of the novel, thus revealing something of the eighteenth-century German reception of Shakespeare's plays. It is Wilhelm who speaks the following words in the novel, generally considered to represent Goethe's views:

J. W. VON GOETHE: from Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship

The time is out of joint, O curs'd spite,

That ever I was born to set it right!

In these words, I imagine, will be found the key to Hamlet's whole procedure. To me it is clear that Shakespeare meant, in the present case, to represent the effects of a great action laid upon a soul unfit for the performance of it. In this view the whole piece seems to me to be composed. There is an oak-tree planted in a costly jar, which should have borne only pleasant flowers in its bosom; the roots expand, the jar is shivered.

A lovely, pure, noble and most moral nature, without the strength of nerve which forms a hero, sinks beneath a burden which it cannot bear and must not cast away. All duties are holy for him; the present is too hard. Impossibilities have been required of him; not in themselves impossibilities, but such for him. He winds, and tums, and torments himself; he advances and recoils; is ever put in mind, ever puts himself in mind; at last does all but lose his purpose from his thoughts; yet still without recovering his peace of mind.

So, usual prompts:

What are the key ideas in Wilhelm's (Goethe's) argument? Summarise them in your own words.

Might any still have resonance today? Why/not?

Is there a memorable, standout phrase here?

Comments

Post a Comment